Almost four years ago, I pledged with Giving What We Can. Members pledge 10% of their incomes to the best charities they can find (with students and those with no income pledging 1% of their spending money).

In the time since, I've felt good about making this commitment. I like having it as part of my routine, something that I know is part of my plan in the years to come. It's a confirmation of what I value—a safe and healthy life not just for me and mine, but for all families around the world. And I've enjoyed the connections with other people who have made this choice.

I'm also a fan of mini-pledges for people who aren't sure about their long-term plan. For a year, or a month, or a semester, make a plan for how much you will donate. See what it's like. Afterwards, maybe it will feel like a good amount. Maybe you'll realize you want to cut back on giving next time. (Jeff and I did that the year we forgot about taxes when making our budget!) Or maybe you'll decide you want to ramp up to something more ambitious. In any case, you'll learn something about how you handle money, and you'll be acting intentionally instead of haphazardly. If you want, you can sign up for "Try Giving" on the Giving What We Can site.

The pledge.

This year I'll be giving largely to the Against Malaria Foundation.

Wednesday, December 16, 2015

Thursday, November 19, 2015

An embarrassment of riches

People interested in effective altruism come from many different backgrounds. I know people whose families expected them to become lawyers or businesspeople, and others whose families would be appalled if they went into something so "money-grubbing."

This post is primarily aimed at those of us who grew up in cultures that emphasized a certain style of simplicity. In some cases I think it can be an advantage, for example, because it's easier to live below our means. But in other cases I think it leads us into bad decisions that prioritize our personal purity above the well-being of others.

....

I'll start with an illustration from history. Jane Addams, the founder of social work, spent her life striving to improve the conditions of poor immigrants and particularly working-class women in Chicago. In 1896, she traveled to Russia to meet with author Leo Tolstoy, whose ideas on solidarity with laborers had impressed her. Both Addams and Tolstoy struggled with how to deal with their privileged backgrounds; Tolstoy was a count and Addams had inherited a fortune as a young woman. Tolstoy, who was living on his family's estate dressing like a peasant and participating in the farm work, began the meeting by criticizing Addams' stylish dress. He urged her to follow him in taking up manual labor rather than spending all her time on administration.

When Addams returned to the large settlement house she ran, she was determined to spend part of her workday in the bakery there rather than in her office. (Reminds me of the Undercover Boss reality show in which CEOs work as janitors for two weeks.)

But she grew frustrated with the inefficiency of spending part of her day as baker rather than director. “The half dozen people invariably waiting to see me after breakfast, the piles of letters to be opened and answered, the demand of actual and pressing human wants—were these all to be pushed aside and asked to wait while I saved my soul by two hours’ work at baking bread?” (Twenty Years at Hull House, p. 197) She decided that she could do more for her neighbors by continuing her administrative work than by sharing in their manual labor.

I think Addams gets at an ongoing problem with tendencies to act or appear a certain way rather than accomplishing anything in particular. (Certainly leftists and liberals are not the only ones to fall into this, but I'll focus on us here.)

Tracy Kidder's book about doctor and humanitarian Paul Farmer cites him talking with other Partners in Health staff about "the goofiness of radicals thinking they have to dress in Guatemalan peasant clothes. The poor don't want you to look like them. They want you to dress in a suit and go get them food and water."

I have a friend who gives away much of his income but realized he needed to spend money on a nice suit to meet with people who care about that sort of thing and influence their giving. "Saving" money by not buying a suit would actually have been a loss for the people he intends to help.

.....

Some of us come from religious traditions that emphasize voluntary simplicity and solidarity with the poor. I'm interested in the ways that this can help or hinder us in actually helping others.

I've enjoyed reading some of the thoughts of a Franciscan friar on voluntary poverty. The Franciscan order was founded largely in response to the opulent lifestyle of the 13th-century Italian upper classes, and material simplicity has been an important part of their tradition ever since. But the writer, Brother Casey Cole, questions whether friars should take solidarity so far as to shoulder the difficulties that come with being involuntarily poor, like buying low-quality appliances that break because you can't afford ones that last longer.

I spent 10 years active in Quaker communities, a tradition which emphasizes simplicity. The main text of each regional Quaker group includes "queries," or questions for reflection, on many topics. One group asks:

I love this approach to simplicity as freedom. Other than my Apartment Therapy habit, I think Jeff and I have been much happier by not letting media dictate our desires too much. Particularly as a parent, I'm wary of the ways we can be led into "needing" things that don't actually improve our quality of life.

But I've also seen the idea of material simplicity extended farther than I think makes sense. At one point Quakers were going around policing the width of each other's hat brims lest somebody have one that was not "plain" enough. And today I think people sometimes slip into policing material possessions, particularly technology, rather than looking at whether these possessions actually improve our lives.

I know people who still look down at smartphones as an unnecessary luxury. As a person who takes public transit, getting a smartphone has changed the way I travel—there's much less getting lost, less rushing to catch a bus only to find it's running late. This material possession makes my life simpler and better. (I notice Brother Cole, quoted above, said his laptop and iPhone are the material possessions most important to him.)

I've seen articles explaining why so many refugees carry smart phones—far from being a luxury, they are a vital source of information and connection to loved ones. Cell phone ownership even among the very poor in Africa has made it possible for them to do everything from transferring money without access to a brick-and-mortar bank, to tracking cattle gestation periods, to verifying that anti-malarial drugs are real and not counterfeit. The way that technology enriches lives from Syria to San Francisco is something I'd like to embrace, not scorn.

.....

John Wesley, founder of the Methodist church, gave his sermon "The Use of Money" many times throughout the 18th century. In it, he advises followers not to reject money, but to use it wisely. "The fault does not lie in the money, but in them that use it. It may be used ill: and what may not? But it may likewise be used well. . . . By it we may supply. . . a defence for the oppressed, a means of health to the sick, of ease to them that are in pain."

Wesley urges followers to "gain all you can" without sacrificing their health or engaging in immoral action, "save all you can" by living simply, and then "give all you can." The sermon is the first known proposal of "earning to give."

.....

But those of us who came from traditions emphasizing simplicity (whether via religion or general hippie culture) were often taught to distrust money. "Money is the root of all evil," we heard, rather than the full quotation "The love of money is the root of all evil."

My mother spoke proudly of the low-paying professions her family tended toward: "Farmers, ministers, teachers, musicians—if it pays badly, we've done it!"

When I started to consider earning to give (earning more in order to donate more), I kept noticing a reaction of disgust to the idea of having a high-paid job. I couldn't get away from my vision of "rich people" as bad and greedy people. The idea of being associated with them, for example by going into law and then donating most of my earnings, turned my stomach. That attitude isn't helpful, and I don't want to pass it on to my children.

I think some of this comes from embarrassment about the privilege I have. I grew up in a rich country with parents who could give me everything I needed. I have a college education, I'm healthy, and I'm able to do many things I set my mind to. I got lucky in a lot of ways, and I'm sad that not everyone has these things.

But squandering this privilege by pretending I don't have it would not help anyone except me. It might make me feel better, but me feeling better about my privilege is not the point. I could be a good hippie and spend my days volunteering at the local library and my evenings making pottery in my basement. No one could accuse me of making things worse, but I would hardly be making things better for people in extreme need. I think we should be less like the ascetic Tolstoy barefoot in the woods, and more like Jane Addams using her wealth, connections, education, and skills for the benefit of others.

If we want to make a better and fairer world for everyone, we should use every tool we have—including money—to do so.

This post is primarily aimed at those of us who grew up in cultures that emphasized a certain style of simplicity. In some cases I think it can be an advantage, for example, because it's easier to live below our means. But in other cases I think it leads us into bad decisions that prioritize our personal purity above the well-being of others.

....

I'll start with an illustration from history. Jane Addams, the founder of social work, spent her life striving to improve the conditions of poor immigrants and particularly working-class women in Chicago. In 1896, she traveled to Russia to meet with author Leo Tolstoy, whose ideas on solidarity with laborers had impressed her. Both Addams and Tolstoy struggled with how to deal with their privileged backgrounds; Tolstoy was a count and Addams had inherited a fortune as a young woman. Tolstoy, who was living on his family's estate dressing like a peasant and participating in the farm work, began the meeting by criticizing Addams' stylish dress. He urged her to follow him in taking up manual labor rather than spending all her time on administration.

When Addams returned to the large settlement house she ran, she was determined to spend part of her workday in the bakery there rather than in her office. (Reminds me of the Undercover Boss reality show in which CEOs work as janitors for two weeks.)

But she grew frustrated with the inefficiency of spending part of her day as baker rather than director. “The half dozen people invariably waiting to see me after breakfast, the piles of letters to be opened and answered, the demand of actual and pressing human wants—were these all to be pushed aside and asked to wait while I saved my soul by two hours’ work at baking bread?” (Twenty Years at Hull House, p. 197) She decided that she could do more for her neighbors by continuing her administrative work than by sharing in their manual labor.

I think Addams gets at an ongoing problem with tendencies to act or appear a certain way rather than accomplishing anything in particular. (Certainly leftists and liberals are not the only ones to fall into this, but I'll focus on us here.)

Tracy Kidder's book about doctor and humanitarian Paul Farmer cites him talking with other Partners in Health staff about "the goofiness of radicals thinking they have to dress in Guatemalan peasant clothes. The poor don't want you to look like them. They want you to dress in a suit and go get them food and water."

I have a friend who gives away much of his income but realized he needed to spend money on a nice suit to meet with people who care about that sort of thing and influence their giving. "Saving" money by not buying a suit would actually have been a loss for the people he intends to help.

.....

Some of us come from religious traditions that emphasize voluntary simplicity and solidarity with the poor. I'm interested in the ways that this can help or hinder us in actually helping others.

I've enjoyed reading some of the thoughts of a Franciscan friar on voluntary poverty. The Franciscan order was founded largely in response to the opulent lifestyle of the 13th-century Italian upper classes, and material simplicity has been an important part of their tradition ever since. But the writer, Brother Casey Cole, questions whether friars should take solidarity so far as to shoulder the difficulties that come with being involuntarily poor, like buying low-quality appliances that break because you can't afford ones that last longer.

I spent 10 years active in Quaker communities, a tradition which emphasizes simplicity. The main text of each regional Quaker group includes "queries," or questions for reflection, on many topics. One group asks:

- Is your life marked by simplicity?

- Are you free from the burden of unnecessary possessions?

- Do you refuse to let the prevailing culture and media dictate your needs and values?

2003 Faith and Practice of Northwest Yearly Meeting

I love this approach to simplicity as freedom. Other than my Apartment Therapy habit, I think Jeff and I have been much happier by not letting media dictate our desires too much. Particularly as a parent, I'm wary of the ways we can be led into "needing" things that don't actually improve our quality of life.

But I've also seen the idea of material simplicity extended farther than I think makes sense. At one point Quakers were going around policing the width of each other's hat brims lest somebody have one that was not "plain" enough. And today I think people sometimes slip into policing material possessions, particularly technology, rather than looking at whether these possessions actually improve our lives.

I know people who still look down at smartphones as an unnecessary luxury. As a person who takes public transit, getting a smartphone has changed the way I travel—there's much less getting lost, less rushing to catch a bus only to find it's running late. This material possession makes my life simpler and better. (I notice Brother Cole, quoted above, said his laptop and iPhone are the material possessions most important to him.)

I've seen articles explaining why so many refugees carry smart phones—far from being a luxury, they are a vital source of information and connection to loved ones. Cell phone ownership even among the very poor in Africa has made it possible for them to do everything from transferring money without access to a brick-and-mortar bank, to tracking cattle gestation periods, to verifying that anti-malarial drugs are real and not counterfeit. The way that technology enriches lives from Syria to San Francisco is something I'd like to embrace, not scorn.

.....

John Wesley, founder of the Methodist church, gave his sermon "The Use of Money" many times throughout the 18th century. In it, he advises followers not to reject money, but to use it wisely. "The fault does not lie in the money, but in them that use it. It may be used ill: and what may not? But it may likewise be used well. . . . By it we may supply. . . a defence for the oppressed, a means of health to the sick, of ease to them that are in pain."

Wesley urges followers to "gain all you can" without sacrificing their health or engaging in immoral action, "save all you can" by living simply, and then "give all you can." The sermon is the first known proposal of "earning to give."

.....

But those of us who came from traditions emphasizing simplicity (whether via religion or general hippie culture) were often taught to distrust money. "Money is the root of all evil," we heard, rather than the full quotation "The love of money is the root of all evil."

My mother spoke proudly of the low-paying professions her family tended toward: "Farmers, ministers, teachers, musicians—if it pays badly, we've done it!"

When I started to consider earning to give (earning more in order to donate more), I kept noticing a reaction of disgust to the idea of having a high-paid job. I couldn't get away from my vision of "rich people" as bad and greedy people. The idea of being associated with them, for example by going into law and then donating most of my earnings, turned my stomach. That attitude isn't helpful, and I don't want to pass it on to my children.

I think some of this comes from embarrassment about the privilege I have. I grew up in a rich country with parents who could give me everything I needed. I have a college education, I'm healthy, and I'm able to do many things I set my mind to. I got lucky in a lot of ways, and I'm sad that not everyone has these things.

But squandering this privilege by pretending I don't have it would not help anyone except me. It might make me feel better, but me feeling better about my privilege is not the point. I could be a good hippie and spend my days volunteering at the local library and my evenings making pottery in my basement. No one could accuse me of making things worse, but I would hardly be making things better for people in extreme need. I think we should be less like the ascetic Tolstoy barefoot in the woods, and more like Jane Addams using her wealth, connections, education, and skills for the benefit of others.

If we want to make a better and fairer world for everyone, we should use every tool we have—including money—to do so.

Thursday, October 22, 2015

Burnout and self-care

I think effective altruism often runs into questions about self-care and boundaries, and might have a few things to learn from social work.

For people in helping professions (like nurses, therapists, and clergy), training programs often warn against burnout and "compassion fatigue." To prevent this, training emphasizes self-care. Self-care might include exercise, sleep, spending time with loved ones, spiritual practice, hobbies, and (at least among my coworkers) the latest episode of "Scandal." My workplace asks every prospective hire about self-care, because we want someone who has a plan for not burning out.

As a helping professional, you maintain boundaries to protect both yourself (you do not tell clients where you live) and clients (you do not burden them with your personal problems). And often boundaries are something you maintain to keep yourself sane.

One early lesson for me, when I was an intern at a psychiatric hospital, came while sitting and talking with a young patient before I left for the evening. When it was time to catch my bus home, I told him I had to leave. "You get to go home," he said sadly, "but I don't get to go home." I felt awful for him, and later I asked my supervisor if I should have kept him company a little longer. "No," my supervisor said, "Go home when it's time to go home. There will always be someone who wants you to stay. You can't come in here and do a good job if you're worn out from the day before."

To me, that's an example of what one author on burnout calls "boundaried generosity." I will give my best up until this point, and then I will stop. That's what makes high-intensity, compassionate work sustainable.

The same principles are applicable to helping work that isn't face-to-face. I've noticed that some of the highest-achieving people I know in effective altruism take sleep pretty seriously and don't skimp in that area. They've learned it's not worth it. They also seem to genuinely enjoy their time off. Unlike Susan Wolf's specter of the "moral saint," humorless and single-minded, these people know how to have fun.

But younger people in particular seem to struggle with the balance of self-care and altruism. Often after I speak to a student group, someone will tell me they wonder if they're wrong to spend money traveling to visit far-away friends or buying things for the mother that scrimped to send them to college. It's hard to think of a better recipe for burnout than distancing yourself from friends and family! No, I don't recommend cutting out this kind of thing if you want your passion for helping others to last more than a few years.

For me, this was an important reason to make a budget rather than asking "Should I donate this money instead?" every time I was in a checkout line. It was the equivalent of going to work with no plan about when to go home—should I see one more client this afternoon? Three? Five?

Knowing I'm leaving work after 8 hours lets me be whole-hearted in my work during that time. In the same way, having a budget allows me to be whole-hearted both in what I give (because I know that money is only for giving) and in what I spend (because I know that money is only for me and my family).

It is okay to take care of yourself. In fact, it's a really bad idea not to.

For people in helping professions (like nurses, therapists, and clergy), training programs often warn against burnout and "compassion fatigue." To prevent this, training emphasizes self-care. Self-care might include exercise, sleep, spending time with loved ones, spiritual practice, hobbies, and (at least among my coworkers) the latest episode of "Scandal." My workplace asks every prospective hire about self-care, because we want someone who has a plan for not burning out.

As a helping professional, you maintain boundaries to protect both yourself (you do not tell clients where you live) and clients (you do not burden them with your personal problems). And often boundaries are something you maintain to keep yourself sane.

One early lesson for me, when I was an intern at a psychiatric hospital, came while sitting and talking with a young patient before I left for the evening. When it was time to catch my bus home, I told him I had to leave. "You get to go home," he said sadly, "but I don't get to go home." I felt awful for him, and later I asked my supervisor if I should have kept him company a little longer. "No," my supervisor said, "Go home when it's time to go home. There will always be someone who wants you to stay. You can't come in here and do a good job if you're worn out from the day before."

To me, that's an example of what one author on burnout calls "boundaried generosity." I will give my best up until this point, and then I will stop. That's what makes high-intensity, compassionate work sustainable.

The same principles are applicable to helping work that isn't face-to-face. I've noticed that some of the highest-achieving people I know in effective altruism take sleep pretty seriously and don't skimp in that area. They've learned it's not worth it. They also seem to genuinely enjoy their time off. Unlike Susan Wolf's specter of the "moral saint," humorless and single-minded, these people know how to have fun.

But younger people in particular seem to struggle with the balance of self-care and altruism. Often after I speak to a student group, someone will tell me they wonder if they're wrong to spend money traveling to visit far-away friends or buying things for the mother that scrimped to send them to college. It's hard to think of a better recipe for burnout than distancing yourself from friends and family! No, I don't recommend cutting out this kind of thing if you want your passion for helping others to last more than a few years.

For me, this was an important reason to make a budget rather than asking "Should I donate this money instead?" every time I was in a checkout line. It was the equivalent of going to work with no plan about when to go home—should I see one more client this afternoon? Three? Five?

Knowing I'm leaving work after 8 hours lets me be whole-hearted in my work during that time. In the same way, having a budget allows me to be whole-hearted both in what I give (because I know that money is only for giving) and in what I spend (because I know that money is only for me and my family).

It is okay to take care of yourself. In fact, it's a really bad idea not to.

Thursday, October 15, 2015

Sample menus for EA gatherings

This post focuses specifically on food ideas. For more on how to host an effective altruism meetup, see here or here.

After four years of hosting effective altruism dinners, I keep learning things.

Summer menu

Everything is vegan and gluten-free except the key lime pie, but I think it comes off as light and summery rather than restricted.

The food is served cold and can be prepped in advance except the soup, which could still be done in advance and just heated and garnished at the last minute. If you’re still working on the spring rolls when guests arrive, people like helping assemble them. This took longer than I thought, about 90 seconds per roll, including waiting for the wrappers to soak and finding room for trays as we filled them. Do the math and leave yourself enough time.

Fall menu

The problem with having the protein and vegetables all in one stew is that if someone can’t eat peanuts or one of the vegetables, they can’t eat the main dish.

Winter menu

Curry menu

The nice thing is that you can make the curries in advance and heat them up before dinner. If you make the pies in advance or use a store-bought dessert, you could serve this on a weeknight – it might take 40 minutes to heat up the curries and make the rice.

Chili menu

Mexican menu

After four years of hosting effective altruism dinners, I keep learning things.

- At least where I live, EA gatherings tend to attract a lot of vegetarians and vegans. I've basically stopped serving meat at these dinners because so few people ate it.

- People, particularly students, appreciate a home-cooked meal even if it's not fancy.

- Store-bought bread and some kind of stew is an easy way to go. You either need bowls or plates with a rim that will keep the stew in place. If you don't have enough or don't want to do that many dishes, you could use disposable dishes. I host dinners often enough that I bought a lot of Pyrex custard cups to use as soup or desssert bowls for the masses (they don't take up the whole plate, so there's room for your bread or salad as well).

- Test-driving the main dish is a good idea so you know about how many people it serves, etc.

- Make more than you think you need, at least of a few central dishes.

- Newer hosts often forget things (are there cups and something to drink? Utensils? Napkins or something to clean up the inevitable spill? Is there enough toilet paper in the bathroom?)

Summer menu

- Fresh spring rolls

- Peanut dipping sauce

- Red curry coconut soup with mushrooms and tofu

- Key lime pie

- Coconut-lime popsicles

Everything is vegan and gluten-free except the key lime pie, but I think it comes off as light and summery rather than restricted.

The food is served cold and can be prepped in advance except the soup, which could still be done in advance and just heated and garnished at the last minute. If you’re still working on the spring rolls when guests arrive, people like helping assemble them. This took longer than I thought, about 90 seconds per roll, including waiting for the wrappers to soak and finding room for trays as we filled them. Do the math and leave yourself enough time.

Fall menu

- West African Peanut Stew

- Rice

- Store-bought bread

- Apple crisp (vegan or not vegan)

The problem with having the protein and vegetables all in one stew is that if someone can’t eat peanuts or one of the vegetables, they can’t eat the main dish.

Winter menu

- Polenta

- Braised beef with tomatoes

- White bean stew

- Braised kale

- Vanilla ice cream with cherry-wine sauce (just heat up some frozen cherries in red wine with a little sugar)

Curry menu

- Jasmine rice

- Chicken coconut curry

- Chickpea coconut curry

- Indian spiced spinach (palak paneer without the paneer. I took some out before adding the dairy so there was a vegan version.)

- Store-bought naan

- Plain yogurt

- Lassi

- Key lime pie

- Gingerbread

The nice thing is that you can make the curries in advance and heat them up before dinner. If you make the pies in advance or use a store-bought dessert, you could serve this on a weeknight – it might take 40 minutes to heat up the curries and make the rice.

Chili menu

- Vegetarian chili

- Toppings (shredded cheese, sour cream, salsa, diced avocado)

- Cornbread

- Salad

- Orange segments dipped in chocolate Not one I've made yet, but one I enjoyed at someone else's party recently.

Mexican menu

- Nachos

- Tortilla soup

- Soup toppings (tortilla strips, shredded cheese, sour cream, diced avocado)

- Oven quesadillas (vegan and non-vegan) with caramelized onion and roasted red pepper

- Palomas (grapefruit cocktail)

- Ice cream with thawed frozen mangos

The vegan nachos and quesadillas are done with refried beans, salsa, and vegan "cheese" shreds (Daiya brand is the best we've found).

Ice cream and thawed fruit works well because it takes no prep other than thawing a bowl of the fruit, and vegans can eat the fruit even if you can't find vegan ice cream. Berries become a mess when thawed, but ones like cherries and mango stay pretty intact.

Middle Eastern menu

If you're serving pears, buy them enough in advance that they have time to get ripe.

Everything is vegan except the shakshuka and lava cakes. You can do tabbouleh with quinoa if you need it to be gluten-free.

I do the lava cakes in muffin tins, which is way easier than ramekins. You can make them in advance (basically 10 minutes of melting and stirring), refrigerate them, and bake them during the party (they only bake for 12 minutes).

Middle Eastern menu

- Appetizer: pear slices and pistachios

- Falafel

- Pita bread (store-bought)

- Tahini sauce and/or cucumber-yogurt sauce

- Tabbouleh

- Shakshuka (eggs poached in spicy tomato sauce)

- Chocolate lava cakes

- Orange segments dipped in chocolate

If you're serving pears, buy them enough in advance that they have time to get ripe.

Everything is vegan except the shakshuka and lava cakes. You can do tabbouleh with quinoa if you need it to be gluten-free.

I do the lava cakes in muffin tins, which is way easier than ramekins. You can make them in advance (basically 10 minutes of melting and stirring), refrigerate them, and bake them during the party (they only bake for 12 minutes).

Thursday, September 3, 2015

Luck of the draw

Seeing stories about the horrifying conditions Syrian refugees face, I’m thinking once again about how lucky I am to have been born in this country.

As a social worker, some of the clients I work with are immigration detainees waiting to find out if they will be deported.

The descriptions they give of their journeys to this country are harrowing. “I spent three days walking through the mountains. There were snakes.” “In the desert it was freezing at night and hot in the day. We got surprised by immigration officials at night and ran off without our water. My neighbor died.” “You pass corpses in the desert.”

What exactly would make a person take those kind of risks? Sometimes it’s a very specific fear: “After my brother got shot, my parents scraped together the money for the trip and told me to come here.” But often it’s simply to avoid grinding poverty. One man explained the life he left as a corn farmer in Central America: “I think I could make about $8 a day. What kind of life can you have? I can’t get married on that, I can’t raise kids.”

Some of them speak of the difference they were able to make to their families: “My mother depends on money I send her for insulin. I don’t know how I’m going to be able to afford it if I have to go back.” “I’ve been keeping my children in school. School there isn’t free like here: you have to buy uniforms and books.” “When I visited my cousins, I left my clothes with them because they didn’t have decent clothes. That’s how poor they are.”

In short, they’re normal people who want normal things and have gone to extraordinary lengths to get them.

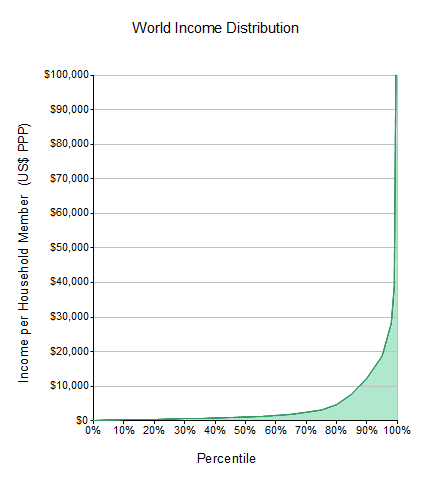

An American at the poverty line ($11,770 a year) is richer than 85% of the world, even after accounting for different costs of living. You can play around with the “How Rich Am I?” calculator.

This is why the idea of prioritizing one’s own neighborhood or nation over others has never made sense to me. No one would choose to be born in the murder capital of the world, or a country undergoing civil war, or a community where people can’t afford to send their children to school. I didn’t do anything to earn my American passport except be born. I didn’t earn the right to be white, or healthy, or from an upper-middle-class family.

And that’s why I want to use my good fortune to make a difference for people who didn’t get so lucky.

As a social worker, some of the clients I work with are immigration detainees waiting to find out if they will be deported.

The descriptions they give of their journeys to this country are harrowing. “I spent three days walking through the mountains. There were snakes.” “In the desert it was freezing at night and hot in the day. We got surprised by immigration officials at night and ran off without our water. My neighbor died.” “You pass corpses in the desert.”

What exactly would make a person take those kind of risks? Sometimes it’s a very specific fear: “After my brother got shot, my parents scraped together the money for the trip and told me to come here.” But often it’s simply to avoid grinding poverty. One man explained the life he left as a corn farmer in Central America: “I think I could make about $8 a day. What kind of life can you have? I can’t get married on that, I can’t raise kids.”

Some of them speak of the difference they were able to make to their families: “My mother depends on money I send her for insulin. I don’t know how I’m going to be able to afford it if I have to go back.” “I’ve been keeping my children in school. School there isn’t free like here: you have to buy uniforms and books.” “When I visited my cousins, I left my clothes with them because they didn’t have decent clothes. That’s how poor they are.”

In short, they’re normal people who want normal things and have gone to extraordinary lengths to get them.

Source: Branko Milanovic, PovcalNet (World Bank)

An American at the poverty line ($11,770 a year) is richer than 85% of the world, even after accounting for different costs of living. You can play around with the “How Rich Am I?” calculator.

This is why the idea of prioritizing one’s own neighborhood or nation over others has never made sense to me. No one would choose to be born in the murder capital of the world, or a country undergoing civil war, or a community where people can’t afford to send their children to school. I didn’t do anything to earn my American passport except be born. I didn’t earn the right to be white, or healthy, or from an upper-middle-class family.

And that’s why I want to use my good fortune to make a difference for people who didn’t get so lucky.

Two new roles

I'm excited to be starting some new things:

- In June I joined the board of GiveWell.

- I'm joining the Center for Effective Altruism's Outreach team. I've wanted to work for them for years, and I'm so glad it became possible without moving to another country! I'll still be doing some social work part-time.

Saturday, August 29, 2015

EA organizations doing policy work

A lot of people, myself included, have felt conflicted about the choice between doing direct work (like health interventions) and trying to change systems. Everyone agrees that well-done policy work can have big impacts, but there's less agreement about how to tell if your work is actually good at changing policy.

At the EA Global conference in California, I was excited to hear more about three EA organizations doing policy work, two of which I hadn't heard of before. Video of all the talks.

Open Philanthropy Project

The Open Philanthropy Project, formerly known as GiveWell Labs, is a joint project of Good Ventures and GiveWell. While GiveWell focuses on recommending giving opportunities with very demonstrated impact, the Open Philanthropy Project explores giving opportunities that have higher risks but higher potential rewards, or that may take a long time to have results.

One of the project's focuses is US policy. Some areas they're looking into include:

You can see Howie Lempel's EA Global talk.

At this point they're not asking for more funding and do not expect to recommend specific giving opportunities for individual donors.

Effective Altruism Policy Analytics

Effective Altruism Policy Analytics is a really interesting shoestring operation run by students at the University of Maryland and economist Richard Bruns. Its goal is "to bring non-partisan, cause-neutral improvements to regulatory action in the United States."

This summer, they've been working on policy comments. The US Government has a comment period on new regulations during which anyone can submit comments and suggestions for change to proposed regulations. The government agency in question must respond to each comment, and may change its regulation if it hears suggestions it likes. EA Policy Analytics has been looking for regulations with room for improvement, but which are cheap to implement and aren't controversial, and submitting comments on them. Some of the topics they've addressed include:

This is definitely in the "experimental" category, but I like it. It's in everyone's interest to have a bunch of slightly better policies, but it's not enough in anyone's interest to do this kind of work for selfish reasons. In other words, it's a perfect project for altruists.

Because they just started, they've only heard back about one of their suggested changes (their suggestion was not taken). They're moving toward choosing regulations more carefully and putting more time into each comment, but they expect that the benefit of even one successful regulation improvement would be worth a lot of failed attempts. Here's an example of a case where a regulation was changed based on comments.

You can see Matt Gentzel's EA Global talk.

They're not asking for donations at this point.

Center for Global Development

The Center for Global Development (CGD) is a "think and do" tank founded in 2001 with the goal of reducing global poverty and inequality via policy change in the US and other rich countries. They work on a broad range of topics including aid effectiveness, climate change, education, globalization, health, migration, and trade.

Some examples of projects:

It's a lot harder for me to tell what's going on here, since it's a much more established organization with a lot more projects than the above two. Because they've tried more things, they have some failures as well as successes on their record.

As with much policy work, it's hard to tell how much success to credit to any one organization. E.g. if they're one of several actors calling for a particular change that is made, would it have happened anyway without them?

You can see Rajesh Mirchandani's EA Global talk (though it is more about policy change in general than the organization in particular).

Unlike the other two organizations described, CDG is actively taking donations. GiveWell has recommended a grant to them in the past.

At the EA Global conference in California, I was excited to hear more about three EA organizations doing policy work, two of which I hadn't heard of before. Video of all the talks.

Open Philanthropy Project

The Open Philanthropy Project, formerly known as GiveWell Labs, is a joint project of Good Ventures and GiveWell. While GiveWell focuses on recommending giving opportunities with very demonstrated impact, the Open Philanthropy Project explores giving opportunities that have higher risks but higher potential rewards, or that may take a long time to have results.

One of the project's focuses is US policy. Some areas they're looking into include:

You can see Howie Lempel's EA Global talk.

At this point they're not asking for more funding and do not expect to recommend specific giving opportunities for individual donors.

Effective Altruism Policy Analytics

This summer, they've been working on policy comments. The US Government has a comment period on new regulations during which anyone can submit comments and suggestions for change to proposed regulations. The government agency in question must respond to each comment, and may change its regulation if it hears suggestions it likes. EA Policy Analytics has been looking for regulations with room for improvement, but which are cheap to implement and aren't controversial, and submitting comments on them. Some of the topics they've addressed include:

- improving compliance with motorcycle helmet laws

- reducing paperwork burden on immigration applicants

- correcting a faulty formula used in funding home weatherization

Because they just started, they've only heard back about one of their suggested changes (their suggestion was not taken). They're moving toward choosing regulations more carefully and putting more time into each comment, but they expect that the benefit of even one successful regulation improvement would be worth a lot of failed attempts. Here's an example of a case where a regulation was changed based on comments.

You can see Matt Gentzel's EA Global talk.

They're not asking for donations at this point.

Center for Global Development

Some examples of projects:

- "Cash on Delivery Aid": proposed a program, currently being piloted by the UK Department for International Development, in which the Ethiopian government is paid a set amount for each student beyond a baseline that completes primary school and takes a grade-10 test. Rather than focusing on "was the money disbursed?" or "how many schools/textbooks/etc. did we buy?" as many aid programs do, this puts the emphasis on results. It respects local autonomy, because the Ethiopian government is free to change its educational system in whatever way it finds best. Results seem to be mixed.

- Popularized advance market commitments for developing vaccines, in which donors make a contract to pay for a successful vaccine if it is developed, providing pharmaceutical companies with financial incentive to develop vaccines. The major success here seems to have been the 2010 pneumonococcal vaccine.

- After Haiti's 2010 earthquake, one of many voices advocating for increased number of Haitian guestworkers to be admitted to the US. Remittances (money sent home) make up 20% of Haiti's GDP.

It's a lot harder for me to tell what's going on here, since it's a much more established organization with a lot more projects than the above two. Because they've tried more things, they have some failures as well as successes on their record.

As with much policy work, it's hard to tell how much success to credit to any one organization. E.g. if they're one of several actors calling for a particular change that is made, would it have happened anyway without them?

You can see Rajesh Mirchandani's EA Global talk (though it is more about policy change in general than the organization in particular).

Unlike the other two organizations described, CDG is actively taking donations. GiveWell has recommended a grant to them in the past.

Sunday, August 2, 2015

Recommend reading

Greetings from the Effective Altruism Global Conference in California! I just got a copy of Will MacAskill's new book about effective altruism, Doing Good Better.

I haven't finished it yet, but I'm finding it enjoyable, with sound advice on career choice, what kinds of causes can do most with your donation, and other steps you can take. You should get a copy! Even if you're already persuaded of everything Will has to say, the examples and the ways he lays out arguments may be helpful in thinking about how to present these ideas to others.

More thoughts about the conference coming soon.

I haven't finished it yet, but I'm finding it enjoyable, with sound advice on career choice, what kinds of causes can do most with your donation, and other steps you can take. You should get a copy! Even if you're already persuaded of everything Will has to say, the examples and the ways he lays out arguments may be helpful in thinking about how to present these ideas to others.

More thoughts about the conference coming soon.

Monday, May 18, 2015

Bread and roses

Both advocates and critics of effective altruism like to contrast arts charities with public health charities. Peter Singer writes on art auctions:

But I think one of our problems is that when we think of "the arts," we think of expensive ones—symphony orchestras playing in concert halls, museums with paintings that cost millions of dollars.

Around the world and throughout history, art has been something more homegrown—people making music in their own families and communities, decorating their belongings and dwellings, composing stories and poetry. There have been many human societies without arts foundations, but none without dance, music, and storytelling.

I was totally charmed to hear some evidence of how promoting human survival also promotes human flourishing: the GiveDirectly theme song. GiveDirectly is a highly rated charity providing cash transfers to poor households in Kenya.

They write: "One of our recipients used part of his transfer to buy instruments and start a band, and wrote this song. We think they sound pretty happy with our service."

A partial translation of the song:

We thank GiveDirectly, the work you are doing in Kenya, Africa is great

GiveDirectly has helped those who were in thatched houses

And now almost everyone is having iron roof house

They have helped everyone who used to sleep in thatched houses,

Now all you see are shining iron roofs.

And once people have the basics—a decent roof, a leg to dance on—just like anyone, they want to cut loose and celebrate.

Thanks to Catriona for pointing out the song and the connection to the arts debate!

In a more ethical world, to spend tens of millions of dollars on works of art would be status-lowering, not status-enhancing. Such behavior would lead people to ask: “In a world in which more than six million children die each year because they lack safe drinking water or mosquito nets, or because they have not been immunized against measles, couldn’t you find something better to do with your money?”This sometimes strikes art-lovers as harsh. After all, they point out, life is about more than just surviving (although this always seems backwards to me, because surviving is obviously a prerequisite for any sort of higher enjoyment, and the unspoken implication is that some people should be left to struggle so others can enjoy the ballet).

But I think one of our problems is that when we think of "the arts," we think of expensive ones—symphony orchestras playing in concert halls, museums with paintings that cost millions of dollars.

Around the world and throughout history, art has been something more homegrown—people making music in their own families and communities, decorating their belongings and dwellings, composing stories and poetry. There have been many human societies without arts foundations, but none without dance, music, and storytelling.

I was totally charmed to hear some evidence of how promoting human survival also promotes human flourishing: the GiveDirectly theme song. GiveDirectly is a highly rated charity providing cash transfers to poor households in Kenya.

They write: "One of our recipients used part of his transfer to buy instruments and start a band, and wrote this song. We think they sound pretty happy with our service."

A partial translation of the song:

We thank GiveDirectly, the work you are doing in Kenya, Africa is great

GiveDirectly has helped those who were in thatched houses

And now almost everyone is having iron roof house

They have helped everyone who used to sleep in thatched houses,

Now all you see are shining iron roofs.

Another piece from a GiveDirectly worker on the role of celebration in the lives of the very poor:

I recently visited Peter, nicknamed Ous Papa, a 50-year-old man and beneficiary of GiveDirectly. Ous Papa had an accident a long time ago and lost one of his legs; as a result, his wife left him. He therefore takes care of his 80-year-old widowed mother alone. They are in absolute poverty -- he has a small grass-thatched house, with mud walls and floor.

He has old crutches that he uses to help him walk and do chores. They are quite old, and therefore difficult to work with. In spite of that, he still wakes up early to work on the farm. When we met, I asked him what he was planning to do with the transfer he was going to receive from GiveDirectly. These were his words: “I would buy a leg.”

I did not understand why he would buy a leg, when he could get a wheelchair that would help him move quickly and easily. He explained that he loves dancing and that he can’t dance in a wheelchair. Furthermore, once he got an artificial leg, he would be able to work, just like anybody else. He said that he would put the rest of the money into his farm, and later get a wife to keep him company and help him take care of his old mother.

I found it really inspiring that a 50-year-old can be in absolute poverty and still dream of dancing.To me, the message is that the basics are not just about the basics. Even the very poor want enjoyment and creativity in their lives—bread and roses, as James Oppenheim put it in his 1911 poem about striking millworkers.

And once people have the basics—a decent roof, a leg to dance on—just like anyone, they want to cut loose and celebrate.

Thanks to Catriona for pointing out the song and the connection to the arts debate!

Monday, April 27, 2015

The Most Good You Can Do

I was excited to see Peter Singer's new book, The Most Good You Can Do.

He's letting the internet decide to donate $10,000 of the royalties. Play the Giving Game to vote!

He's letting the internet decide to donate $10,000 of the royalties. Play the Giving Game to vote!

Sunday, April 12, 2015

Charity begins at home?

Sometimes people ask Jeff and me if we plan to raise our daughter in some special way as an effective altruist. The answer is “not really.” Some have asked if we consider her a sort of recruit, hoping that her future donations will outweigh the cost of raising her. The answer is “definitely not.”

Of course, we hope that Lily will become a kind and generous person. (Currently she’s at the stage of taking other babies’ books from them at the library, but we trust that will change.) But we wouldn't want to count on her donating a certain amount, or curing malaria, or anything else. It doesn't seem very realistic, and pushing her too hard to be like us might backfire and cause her to reject the whole idea.

I've seen some people react with dismay that anyone would give away a large portion of their income while also choosing to become a parent. They don't like the idea of "putting other people before your child."

If Lily really needed anything, we'd do our best to be sure she had it. Even after giving away half our income, we're left with more than the average American family. (And far more than the average world family.) As one friend says, "It's obviously possible to live on this amount of money, because almost everyone does it." So we're at least as able to provide for Lily as most other families you might meet.

And part of raising a child is teaching them that their wants don't always come first. You can't always have the biggest slice of cake, or your friend's toy, or the first turn on the swing when other children are waiting. Learning to share and to prioritize others' needs as well as your own is an important part of learning to live in human society.

I hope that giving will be a normal part of family life as Lily grows up. My mother grew up in a household where her parents tithed 10% of their income, and none of them considered that remarkable. My grandmother taught her children to allocate their 20-cent allowance with "a dime to spend, a nickel to save, and a nickel to give away." There are some attractive children's banks out there with different compartments for saving, spending, investing, and giving. I've also seen homemade ones if you're galled by the idea of paying for a piggy bank.

We hope to teach Lily to be kind in her personal life, and also to think of herself as part of a larger world in which she can help many people (even if she doesn't know them personally).

I like the idea of charity beginning at home. I wouldn’t want it to end there!

Of course, we hope that Lily will become a kind and generous person. (Currently she’s at the stage of taking other babies’ books from them at the library, but we trust that will change.) But we wouldn't want to count on her donating a certain amount, or curing malaria, or anything else. It doesn't seem very realistic, and pushing her too hard to be like us might backfire and cause her to reject the whole idea.

|

| Celebrating one year of being neither effective nor altruistic |

I've seen some people react with dismay that anyone would give away a large portion of their income while also choosing to become a parent. They don't like the idea of "putting other people before your child."

If Lily really needed anything, we'd do our best to be sure she had it. Even after giving away half our income, we're left with more than the average American family. (And far more than the average world family.) As one friend says, "It's obviously possible to live on this amount of money, because almost everyone does it." So we're at least as able to provide for Lily as most other families you might meet.

And part of raising a child is teaching them that their wants don't always come first. You can't always have the biggest slice of cake, or your friend's toy, or the first turn on the swing when other children are waiting. Learning to share and to prioritize others' needs as well as your own is an important part of learning to live in human society.

I hope that giving will be a normal part of family life as Lily grows up. My mother grew up in a household where her parents tithed 10% of their income, and none of them considered that remarkable. My grandmother taught her children to allocate their 20-cent allowance with "a dime to spend, a nickel to save, and a nickel to give away." There are some attractive children's banks out there with different compartments for saving, spending, investing, and giving. I've also seen homemade ones if you're galled by the idea of paying for a piggy bank.

We hope to teach Lily to be kind in her personal life, and also to think of herself as part of a larger world in which she can help many people (even if she doesn't know them personally).

I like the idea of charity beginning at home. I wouldn’t want it to end there!

Tuesday, April 7, 2015

How much to push the envelope?

This sprang out of the last post on how to talk to people about giving.

If you're trying to persuade people, it's unclear how far to push things. I hope there are studies out there on the optimal approach, but I haven't seen them.

John Woolman was an 18th-century American Quaker who was ardent about the abolition of slavery before abolitionism was really a thing. His friends found him kind of embarrassing because he would do things like refusing to use silverware at his friends' houses because silver was mined by slaves, or paying his friends' slaves for their work when they served him dinner. But he was successful in persuading some of his friends to free their slaves, and in retrospect his actions look heroic because he brought abolitionism onto the map.

I once assumed that Woolman was the kind of person who found it easy to do socially provocative things — I think we've all met That Guy at some point. But when I read his account of his life, he actually describes finding it really difficult and embarrassing to break social convention. He did it despite his discomfort, because he believed it was really important. That makes me respect him a lot more.

I often find myself getting annoyed with vegan activists for breaking social convention. Then I wonder if I'm dining with modern day Woolmans.

Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X embody two different strategies about how much to push the envelope. King's civil rights movement was extremely careful to stay within conventional morality and to represent themselves as upstanding, respectable citizens. (Bayard Rustin, who organized the March on Washington, was sidelined due to embarrassment about his being gay. Claudette Colvin was arrested nine months before Rosa Parks for resisting bus segregation in Montgomery, but was not highlighted by the movement because she was unmarried and pregnant. Those decisions sound pretty awful now, but I think they were probably the right thing for that particular movement to do at the time, given that white Americans were not even okay with black ministers in suits eating at lunch counters.)

Malcolm X was not worried about offending white sensibilities, calling King a "chump" and demanding social change rather than going the more incremental route. And yet he, too, was very careful about some aspects of presentation — I challenge you to find a picture of him not wearing a tie. There's one picture of him wearing a dashiki, but he's actually wearing a tie underneath.

It might be good for a movement to have some of both strategies. Some people/organizations play it safer and gain respectability. Others push the envelope. This is probably an argument for having multiple branches/organizations within a movement, so that some can try more radical strategies while other go for more mainstream appeal.

Malcolm X was not worried about offending white sensibilities, calling King a "chump" and demanding social change rather than going the more incremental route. And yet he, too, was very careful about some aspects of presentation — I challenge you to find a picture of him not wearing a tie. There's one picture of him wearing a dashiki, but he's actually wearing a tie underneath.

It might be good for a movement to have some of both strategies. Some people/organizations play it safer and gain respectability. Others push the envelope. This is probably an argument for having multiple branches/organizations within a movement, so that some can try more radical strategies while other go for more mainstream appeal.

Friday, March 13, 2015

How to talk about giving

Recently someone asked me about much to talk about effective giving. Some thoughts:

- Blogging (or other forms of writing) are nice because reading is optional. If I write a blog post and link to it on Facebook, my Facebook friends can either choose to go read it or not. If they're not interested in the topic, it's not awkward in the same way that it could be in conversation. Because I'm not afraid of seeming pushy, I end up saying more in writing than I would in person, with the result that people who are interested can easily find what I have to say on the topic.

- There's value to just casually mentioning that giving is something you do and that's important to you. I think of it kind of like vegetarianism - if you didn't know any vegetarians, it would probably seem like a weird and difficult lifestyle. But once you are in an environment where you know several vegetarians (for many of us, this happens in college), it starts seeming much more feasible and normal. Likewise, if you've never met anyone who gives 10% of their income, that might seem like a freakishly large amount, but once you know a couple of people who do it, you might start to consider it yourself.

- For people with a tight budget, I think donating even a token amount every year is valuable because it lets you talk about your decision. You can say to a friend, "I try to donate some every December, and I was trying to figure out where to give this year. I was reading about [xyz charity] and found out [interesting fact], so I think I'll go with them because..." etc.

- I know a few people whose strategy is to talk about their favorite causes as much as possible and try very hard to persuade people. It's not necessarily a bad strategy — the Mormons have done very well for themselves by having a lot of earnest conversations with a lot of people — but I also think it's okay to take a more relaxed approach.

- If you're excited and ardent about this, it's fine to come across as excited and ardent, but please be careful of being obnoxious or looking like a crackpot.

- Please don't exaggerate your data. I've seen people using very low estimates for the cost to save a life, usually ones that are years out of date. GiveWell used to be a bit more forward with estimates like "It costs $X to save a life with mosquito nets," but after they found serious mistakes in even the best data out there, they're less more cautious about that kind of statement. You should be cautious, too. If you're slinging around numbers like $800 from an essay written years ago, and the current best estimate is more like $3,500, you're not helping the situation.

Saturday, January 3, 2015

Thomas Cannon

I grew up hearing about Thomas Cannon, the "poor man's philanthropist" of my home town. He was a postal clerk known for leaving $1000 checks to strangers. Recently I received a book about him (thank you, David!) and have been enjoying reading about his life.

After his death in 2005, the Washington Post wrote:

He gave away more than $150,000 over the past 33 years, mostly in thousand-dollar checks, to people he read about in the Richmond Times-Dispatch who were experiencing hard times or who had been unusually kind or courageous.

Mr. Cannon supported his wife and himself, their two sons and his charitable efforts on a salary that never topped $20,000 a year. As one of his sons recalled, "There was nothing special about our home life. He went to work every day, helped us with our football and baseball, made sure we were taken care of."

When he retired from the postal service in 1983, he and his wife lived in virtual poverty on his pension. "We lived simply, so we could give money away," he told the Times-Dispatch this year. "People say, 'How can you afford it?' Well, how can people afford new cars and boats? Instead of those, we deliberately kept our standard of living down below our means. I get money from the same place people get money for those other things."